On 18 February 2020, a short yet notable announcement was made by the Trade mark Office of China (CTMO): The Announcement on the Publication of Trade mark Opposition Decisions Online.

As announced, as of 1 January 2020, all the decisions on trade mark oppositions will be published on the China Trade Mark Network, within 20 workings days from the date of post, except under one of the following circumstances:

- Those involving the trade secrets or personal privacy of the parties concerned;

- Parties requested in writing not to make it public, and the Office consider the request reasonable;

- Other special circumstances that the Office deems inappropriate to be disclosed online.

By 6 January 2020, 221 opposition decisions had been published on the said website.

Long overdue, welcome, challenging

China is pretty late in adopting this specific administrative initiative compared to many of its counterparts. The Intellectual Property Office of the United Kingdom (UKIPO), for example, has published opposition decisions on its website since 1998; and as early as 2005, the Benelux Office for Intellectual Property (BOIP) began publishing opposition decisions on its website.

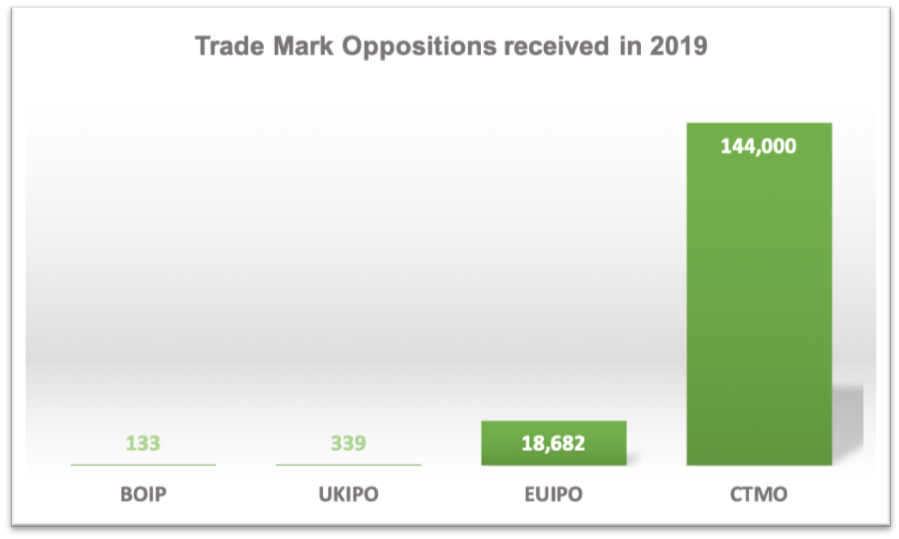

The delay might be somewhat excusable considering that the workload for its preparation must have been enormous in terms of, inter alia, the huge quantity of oppositions filed. In 2019, CTMO received 144,000 trade mark oppositions, which was a far higher number of cases than those received in the aforementioned offices and in the EUIPO. *

The aim of this initiative, as summarised in the opening statement of the announcement, is to „enhance the transparency of trade mark opposition examination work, strengthen social supervision, and promote law-based administration“. These desired-to-realise positive interactions are logical and, in the meantime, quite challenging, given that such a ‘100,000+ per year’ scale of openness and transparency will draw higher requirements on the quality of services from opposition examiners. Specifically, not only must the examiners stably and accountably balance the relationship between ‘the case-by-case approach’ and ‘the uniform standards basis’ in every single case, but they are also likely to receive many questions from the public with regard to, in essence, stare decisis v. the multifactor test.

Moreover, considering that the published decisions will undoubtedly become research materials and sources for big data analyses conducted by tech companies, even more questions will be asked. A likely question would be why a specific opposition decision is not consistent with the predictions and whether the applicability of such predictions needs to be further regulated (which perhaps will spark the rethinking of ‘banning judicial analytics (Article 33 of the Justice Reform Act in France)’ in China.

Answering these questions will require a fair number of explanations, research and adjustments, and will probably lead to lively debates between the CTMO and the public. It does not necessarily mean low-quality work, but it shows that there can sometimes be a gap in understanding between the professionals and everyone else. Normally, the examiners are more knowledgeable on trade mark matters, and in the aftermath of the all-public initiative, they must also be prepared to explain their decisions in a way that is both reasonable and understandable. It will be interesting to see how the CTMO will handle all the challenges. It is believed that these interactions – whether amicable or intense – if they are conducted transparently, will eventually benefit both the current common understanding and the future quality of trade mark administration in China.

Malicious opposition filers – nowhere to hide

Filing oppositions is a powerful right that should never be overlooked or underestimated. This is particularly the case in the current Chinese trade mark system, which, from my point of view, has a prominent flaw: the cost of filing malicious opposition is too low.

Article 33 of the Chinese Trade mark Law provides that,

If a holder of prior rights or an interested party holds that the trade mark application announced upon preliminary review is in violation of the second or third paragraph of Article 13(2) and (3), Article 15, Article 16(1), Article 30, Article 31, or Article 32 of this Law, he may, within three months from the date of the preliminary review announcement, raise objections to the CTMO. Any party that is of the opinion that the aforesaid trade mark application is in violation of Article 4, Article 10, Article 11, Article 12, or Article 19(4) of this Law may raise objections to the Office within the same three-month period. If no objection is raised upon expiry of the announcement period, the Office shall approve the application, issue the certificate of trade mark registration, and make an announcement thereon.

In short: Article 33 says that, if, upon preliminary review, an announced trade mark application is in violation of your private rights, e.g., prior trade mark rights or copyrights, you, or the person of interest, are entitled to file an opposition; if the application itself were never registered as a trade mark (e.g. due to bad-faith, absolute grounds), then anyone could file an opposition against it.

Article 33 does not explicitly require that a ‘(party with) real interest’ or ‘qualified reasoning’ file an opposition. Thus, filing opposition in China is not a difficult task – which can be seen as readily exploitable loopholes, by malicious opponents.

What’s worse is that, unlike the situation in the EU, where the losing party bears all costs of the opposition (including both the opposition fee and the attorney fee, to a certain extent), in China, the only mandatory cost for the opponent is the official opposition fee (CNY 500 or approx. EUR 66). In contrast with this extremely low cost to the opponent, the applicant must bear the much higher costs in terms of time, considering that all the filed oppositions must be examined by the Office and that each of these will take months.

It is therefore submitted that the transparency brought by the announcement may help prevent future abuses of opposition rights, as ‘sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants’ (U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis in his 1932 article ‘What Publicity Can Do’), and that the CTMO should introduce punitive damages towards opponents who lose. Since the announcement, such proposals have been on the rise.

That said, on the bright side, the opposition procedure itself certainly can be used for good – voices of a large number of honest opponents must be heard as well. The reform of the opposition procedure then must require much in-depth and extensive work, which will prompt questions like ‘Should the judgement of bad-faith or not be decided merely by the outcome of opposition?’ or ‘If not, how many oppositions filed by a party within how long a period shall be deemed to be bad-faith?’ These questions await answers, and considerable efforts will need to be put in place.

In conclusion, given some time, this initiative will surely provide a significant amount of data and spark discussions that could help expose problems worthy of correction and improve the quality of work. It will be interesting to see what will come out of this rich field. All in all, excited, wary or whatsoever, the adventure has begun.

* Source of data: EUIPO Statistics in European Union Trade marks, and the statistics published on the respective competent authorities: National Intellectual Property Administration of China (CNIPA), UKIPO and BOIP.